“She got a divorce because of her ambition and love of money,” shopkeeper Dulce Álvarez told IPS, about Guatemalan former First Lady Sandra Torres’ decision to end her marriage in order to sidestep the legal bar to the president’s family members running for the presidency.

Like Álvarez, various Guatemalan women’s groups and their leaders said the controversial decision by the wife of President Álvaro Colom, whose term ends in 2012, was “unethical”, although others have viewed it as a reaction to “the marginalisation women are subjected to in this country.”

Article 186 of the constitution forbids relatives up to the fourth degree of consanguinity and the second of affinity to the president (or the vice president if he or she is acting as president) to stand as a presidential candidate.

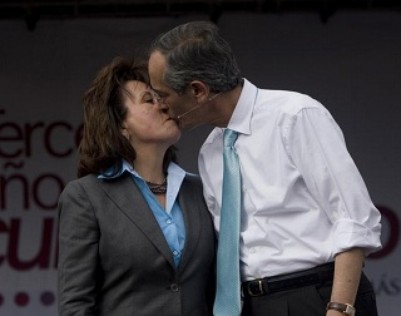

Colom and Torres were married eight years ago when they were both politicians. Their divorce opens the way for Torres to run for the presidency in the coming Sept. 11 elections, in a country where democracy is still in the process of consolidation, and where Colom cannot stand for immediate reelection.

The divorce was filed in March and granted in April, but has been tied up in a web of appeals, suspensions, rulings and overrulings, the latest of which favours Torres. On May 12 the constitutional court overturned the decision of a lower court that had provisionally suspended the couple’s legal separation.

Torres, 51, was proclaimed presidential candidate May 8 by a coalition between the governing social democratic National Union of Hope (UNE) and the centre-right Great National Alliance (GANA). Early polls place her second in terms of voting intentions.

The Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) opened the process for formal candidate registration this month, and it closes Jul. 2. Torres began the registration process May 10 but its formal approval is still incomplete.

“It doesn’t seem ethical to get a divorce when the reason is not relationship break-up but just to qualify as a presidential candidate,” Raquel Zelaya of the Association for Research and Social Studies (ASIES) told IPS.

“Sandra (Torres’) legitimacy is very much undermined, because in order to govern one must have deep respect for the letter and the spirit of the law,” she added.

Nor is this the right way to overcome political discrimination against Guatemalan women, Zelaya said. “Women’s struggles must use legal means, but this (Torres’ divorce) is not an approach I would expect women to take,” she said.

Women’s political participation in this Central American country of 14 million people is limited. In the single-chamber Congress, only 19 out of 158 lawmakers are women, and the Inter-Parliamentary Union ranks Guatemala 90th out of 129 countries by their percentage of women legislators.

The situation is even worse in other branches of government. In the Supreme Court, there is one woman among the 13 judges, and out of the country’s 333 municipalities, only six are headed by a woman mayor.

Unlike the majority of Latin American countries, Guatemala does not have a quota law to improve women’s representation in elected posts.

Nobel Peace Prize winner Rigoberta Menchú was also declared a presidential candidate by the indigenous Winaq political movement and a leftwing coalition. In 2007, Menchú became the first indigenous woman to stand for the presidency of a Latin American country.

Nineth Montenegro, a lawmaker for the centre-left Encounter for Guatemala, told IPS the barriers women face do not justify breaking the law to attain positions of power.

“The divorce would not be a problem were it not for the motive behind it. We all have the right to marry and get divorced. But here it would seem that her marriage conveniently brought the benefits of being first lady, and now her divorce is being used to become a candidate,” she said.

Montenegro praised other women’s struggles in the history of Guatemala. For instance, “the first women workers fought for decent hours and wages and resisted the dictatorships of Jorge Ubico (1931-1944) and Manuel Estrada Cabrera (1898-1920),” she said.

“Going to any lengths to achieve one’s goals is questionable, because as well as skills as a stateswoman, a great deal of fairmindedness, tolerance and respect for the law are needed to run a country,” Montenegro said.

But some groups of women have taken a lighter view of the Colom-Torres divorce. “The law has been flouted, but we think this is not the most worrying aspect of the current situation,” Mayra Alvarado, of the National Union of Guatemalan Women (UNAM-G), told IPS.

“These women have had to earn greater merit than their male counterparts to reach decision-making posts, like Sandra Torres for example, in a patriarchal, authoritarian and militaristic system,” she said.

“It’s only in the past 46 years that women have been eligible to vote and be elected in Guatemala, and rape within marriage went unrecognised until recently,” she said.

Rosario Escobedo of the Women’s Sector, an alliance of non-governmental women’s organisations, told IPS that the first couple’s divorce “is an electoral ploy,” but it is still a divorce, which “everyone has a right to.”

She emphasised that women have been sidelined in Guatemalan politics, and given the least desirable posts by the parties. In any case, “more women in politics does not guarantee a change in women’s daily lives, especially if there are no programmes to make long-term improvements in women’s lives,” she said.

Torres, for her part, says “I have the right to vote and to stand for election. I’m divorcing the president but I’m marrying the people,” a phrase she uses repeatedly in rallies.

Still formally a presidential hopeful, Torres had unprecedented power as coordinator of the Social Cohesion Council created by Colom, where she managed millions of dollars in funding for social programmes and participated in cabinet meetings. She still wears her wedding ring and, according to opponents, she is living at the presidential residence.

The organisation Alternativa Renovadora de Abogados y Notarios got a provisional suspension of the presidential divorce, alleging the separation was fraudulent and its real reason was to enable Torres to stand for president.

This measure was overruled by a decision of the constitutional court, but the legal battle is not over, and a group of those who wrote the present constitution have threatened to impeach the president if Torres’ candidacy is formally approved, on the charge of attempted violation of the constitution.

Torres has complained that she is “criticised for what she has done and what she hasn’t done,” while the 59-year-old Colom declares that she faces “no constitutional bar” to aspiring to succeed him, even though in April 2010 he said that divorce for political ends would be “immoral.”

In the Latin American region, Argentina, Brazil and Costa Rica currently have a woman president, and Peru may join them in July. (END)

Source: IPS News

[…] GUATEMALA Ethics and politics get divorced […]